We’ve compiled this information on privacy and cybersecurity legislation in the US.

It’s designed as a high-level overview with links to sources for further research. Please read our disclaimer at the bottom of this page.

Privacy

In 2019, the US data privacy framework changed significantly with the emergence of the California Consumer Privacy Act. This created a significant compliance burden for most businesses that collect personal information about California residents.

Since then, activity at the state level has increased as more states look to establish data privacy laws in the absence of a comprehensive data privacy law at the federal level. As of 2024, under half of States have passed comprehensive data privacy laws.

The “patchwork" of state privacy laws may be becoming unmanageable for U.S. companies. Many chose to manage their privacy obligations by focusing on compliance with the California privacy law, considered the most complex in the country.

Recent events, however, may have broken that compliance model with recent privacy laws in Maryland, Minnesota, and Vermont — each of which departs considerably from the dominant models of U.S. state privacy law and increases the compliance burden for U.S. companies.

Privacy

AI

Currently, there is no comprehensive federal legislation or regulations in the US that govern the development of AI or specifically prohibit or restrict their use. However, there are existing federal laws that concern AI, albeit with limited application. A non-exhaustive list of key examples includes:

- Federal Aviation Administration Reauthorization Act, which includes language requiring review of AI in aviation.

- National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2019, which directed the Department of Defense to undertake various AI-related activities, including appointing a coordinator to oversee AI activities.

- National AI Initiative Act of 2020, which focused on expanding AI research and development and created the National Artificial Intelligence Initiative Office that is responsible for “overseeing and implementing the US national AI strategy.”

Nevertheless, various frameworks and guidelines exist to guide the regulation of AI, including:

- The White House Executive Order on AI (titled Safe, Secure, and Trustworthy Development and Use of Artificial Intelligence) which is aimed at numerous sectors, and is based on the understanding that “harnessing AI for good and realizing its myriad benefits requires mitigating its substantial risks.” The executive order requires developers of the most powerful AI systems to share safety test results and other critical information with the U.S. government.

- The White House Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights, which asserts guidance around equal access and use of AI systems. The AI Bill of Rights provides five principles and associated practices to help guide the design, use and deployment of “automated systems” including: Safe and effective systems, Algorithmic discrimination and protection, Data privacy, Notice and explanation, Human alternatives, consideration and fallbacks.

- Several leading AI companies (e.g., Adobe, Amazon, IBM, Google, Meta, Microsoft, Open AI, and Salesforce) have voluntarily committed to “help move toward safe, secure, and transparent development of AI technology.” These companies committed to internal/external security testing of AI systems before release, sharing information on managing AI risks and investing in safeguards.

- The Federal Communications Commission issued a declaratory ruling stating that the restrictions on the use of “artificial or pre-recorded voice” messages in the 1990s era Telephone Consumer Protection Act include AI technologies that generate human voices, demonstrating that regulatory agencies will apply existing law to AI.

AI

The Illinois Biometric Information Privacy Act (BIPA)

As tools to collect biometric data become more advanced and more widely used, laws like the Illinois Biometric Information Privacy Act (BIPA) are being introduced and considered to prevent private entities from collecting biometric information without disclosure and consent.

In 2008, Illinois became the first state to enact a biometric data privacy law. The law requires entities that use and store biometric identifiers to comply with certain requirements. The law also provides a private right of action for recovering statutory damages when they do not.

BIPA specifies that “biometrics are unlike other unique identifiers that are used to access finances or other sensitive information. For example, social security numbers, when compromised, can be changed. Biometrics, however, are biologically unique to the individual; therefore, once compromised, the individual has no recourse, is at heightened risk for identity theft, and is likely to withdraw from biometric-facilitated transactions.”

BIPA defines a “biometric identifier,” in part, as “a retina or iris scan, fingerprint, voiceprint, or scan of hand or face geometry.”

Penalties for noncompliance range from:

- $1,000.

- Actual damages for negligent violations to $5,000.

- Actual damages for intentional or reckless violations, plus litigation costs and other relief, like an injunction against use.

BIPA provides a private right of action for violations, and it is a strict liability statute.

A wave of lawsuits, largely putative class actions, followed BIPA's passage. Most were brought by former or current employees whose employers used fingerprints or handprints for timekeeping. But customer suits have yielded high-dollar verdicts and settlements. For instance, a jury in the first ever BIPA trial (October 2022) found that defendant BNSF Railway Company recklessly or intentionally violated BIPA 45,600 times (once per class member) when it required drivers to register and provide fingerprints each time they used an automated gate system to enter the railyard. The verdict resulted in a $228 million award for the plaintiffs. Richard Rogers v. BNSF Railway Co.

The Illinois Biometric Information Privacy Act (BIPA)

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC)

In July 2023 the Securities and Exchange Commission adopted rules requiring registrants to disclose material cybersecurity incidents they experience and to disclose on an annual basis material information regarding their cybersecurity risk management, strategy, and governance. The Commission also adopted rules requiring foreign private issuers to make comparable disclosures.

The rules require registrants to disclose any cybersecurity incident they determine to be material and to describe the material aspects of the incident's nature, scope, and timing, as well as its material impact or reasonably likely material impact on the registrant. This will generally be due four business days after a registrant determines that a cybersecurity incident is material.

The rules also require registrants to describe their processes for assessing, identifying, and managing material risks from cybersecurity threats, as well as the material effects from cybersecurity threats and previous cybersecurity incidents. Registrants are required to describe the board of directors’ oversight of risks from cybersecurity threats and management’s role and expertise in assessing and managing material risks from cybersecurity threats.

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC)

A quick disclaimer about this advice

The information here is not, and doesn’t intend to be, legal advice.

All information, content, and materials are for general information only. The information may not be the most up-to-date, legally or otherwise and may not be exhaustive. This website contains links to other websites – these are for convenience; Brit does not recommend or endorse the contents of the third-party sites.

A quick disclaimer about this advice

Our cyber products

Insights

Read the latest insights from our cyber security partners.

Insights

Overcoming barriers to buying Cyber Insurance for SMEs

Read moreGoodbye Windows 10

Read more

The Open-Source Threat: What You Need to Know About OSINT

Read more

Tech E&O Explained: Risks, Coverage & Insights for Brokers

Read more

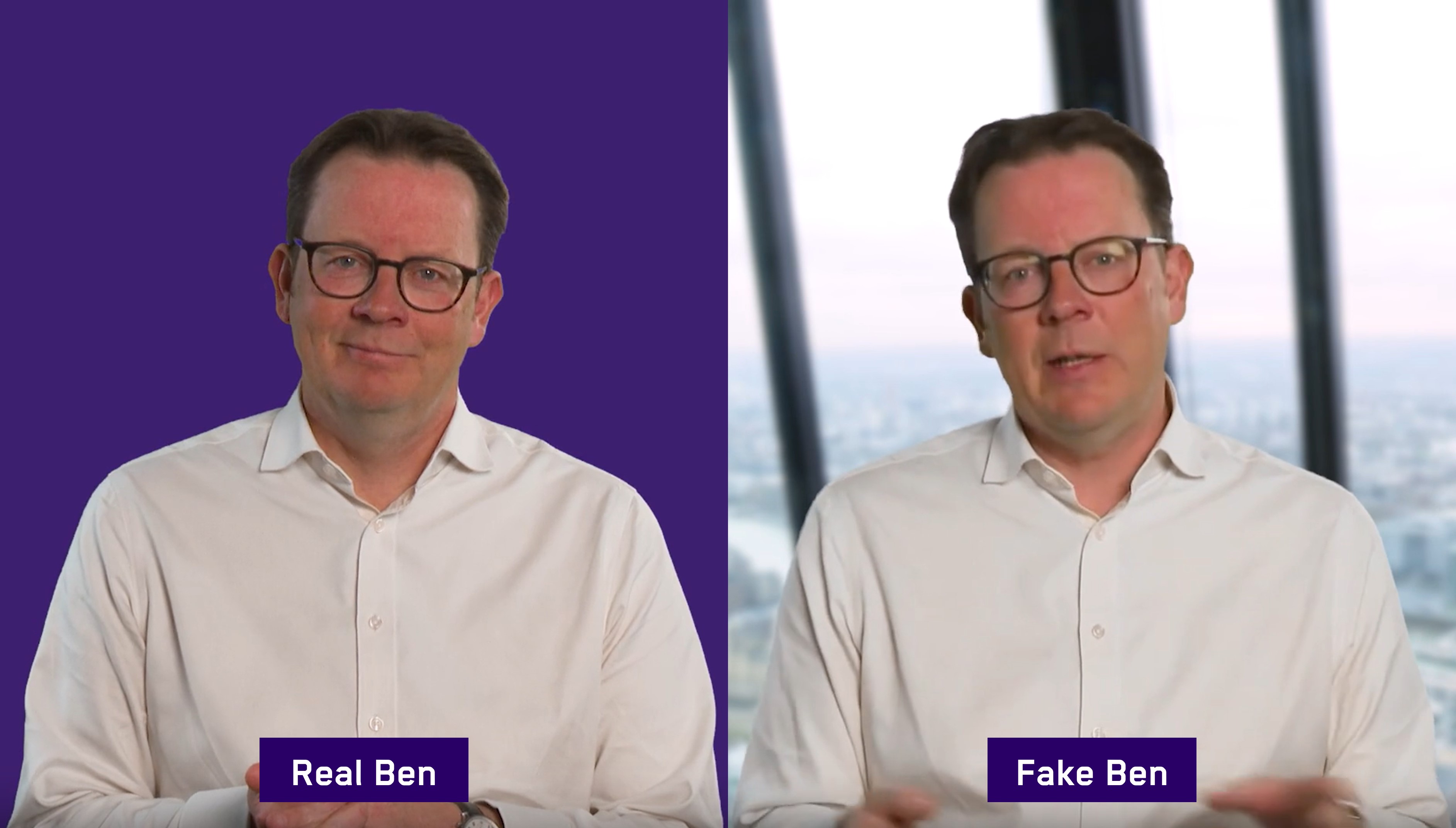

Dabbling with deepfakes

Read more

Consistently Inconsistent

Read moreBrit Acclaimed in the 2025 IBUK 5-Star Cyber

Read more

Operational Technology (OT): Protecting Critical Systems in a Connected World

Read more

Digital Forensics: Managing a Digital Crime Scene

Read more

Breach response: leave it to the experts

Read more

Risk Versus Reward: Using AI In Business

Read more

How cybercriminals exploit MFA reset prompts

Read more